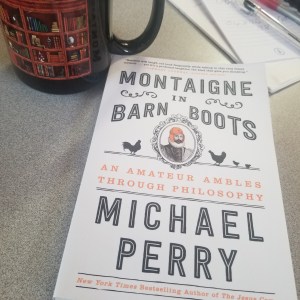

As a more focused companion to The Socrates Express I wrote about earlier, Michael Perry’s Montaigne in Barn Boots covers just one of Weiner’s philosophers: Michel de Montaigne (more formally, Michel Eyquem, Seigneur de Montaigne, 1533-1592), often referred to as the father of the modern essay. Oddly enough, since he’s such a vaunted name these days – and who isn’t put off by such authority? – thanks to Perry’s dissection of his works, I find common ground, and reassurance.

Unlike so many thinkers I’ve tried to study, Perry says, “You read Montaigne, you feel like you have a friend” (10). Yes, he tackled philosophically-dense subjects like “freedom, power, religion, the nature of existence” and more (5). But those weighty issues are interspersed with essays on “drunkenness, radishes, hairstyles, impotence, aromatherapy” (6) and other more mundane topics, while “catch[ing] himself in the act of thinking” (Burke, qtd. at 10).

So often, today’s essayists talk about “thinking on the page”; Montaigne beat them all to that practice. And Perry shares his own journey of thoughtful discovery as he explores the Frenchman’s words. Similar to Montaigne’s feeling about his writing, Perry says, “My keystrokes are short-lived sparks sent flittering into the void, my books a match struck in a monsoon” (3). Phew! I feel like I’ve been given permission to not write for the ages, but just for me, for now. It’s okay if my words wander and stumble and sometimes fall flat. This blog is my thinking on the page.

Like Perry and Montaigne before him, “I offer things in print I would never offer in conversation” (19). Not only does writing give me a chance to rethink and revise and polish, but my awful tendency of brain freeze when put on the spot means I’m not much good at formal argument.

Thankfully, when I struggle to remember those words of wisdom I’ve read in any one of the many philosophy books on my shelf, whether they be Socrates’ or Thoreau’s or Beauvoir’s, I’m also in good company with Montaigne: “I eternally fill…but little or nothing stays with me” and with Perry: “I am lost without access to the original source” (71). That’s why I keep the books handy, complete with Post-it flags and annotations and underlining. And why I write and not debate.

Montaigne’s Essais has been described as “a book that is professedly a record of change” where “many apparent contradictions are really changes of opinion” (210). As much as I enjoy Perry’s effort, “The best book about Montaigne n was written long ago…by Montaigne himself” (Frame qtd. at 214). Guess it’s time to find an accessible translation of Essais (high school French is long gone), join Perry, and “Take up the cause of uncertainty” (215).

Leave a comment